The first version of FileMaker Cloud was released back in March 2017 and it brought something quite new to the platform. It allowed to consume relatively little resources while being lightly used, and at the same time was ready for rapid burst of power when you needed it. Based on the user feedback and experience, which included steep learning curve to set up and administer AWS, FileMaker (now Claris) announced its successor at the FileMaker Developer Conference 2019. FileMaker Cloud 2, finally released on the 30th of October, removes all the technical difficulty and delivers an easy to use hosting platform for any custom FileMaker app. All the complexity is handled by Claris.

But how fast or slow is it and what should you know before deciding to throw away your old Mac mini you're using to run FileMaker Server and move your databases to FileMaker Cloud? Let me put the other aspects, such as cost or security, aside for now, and focus solely on performance.

Just like in the past few years, this fall I was running thousands of performance tests to present their results at the European FileMaker developer conferences. I focused my tests primarily on comparing FileMaker 18 with FileMaker 17. However, since FileMaker Cloud 2 was going to be released soon after the conferences, there was no better time to include FileMaker Cloud in my tests as well.

I managed to get a trial access to FileMaker Cloud just a day before leaving my home for the trip to the conferences, but the results were worth the effort. Here's a short excerpt from my FileMaker Konferenz session:

The results I got surprised me so much that I had to run some tests even between the conferences and some aftewards in order to really understand what I found out. Now I can share my discoveries with you below.

The (kind of) Expected Results

FileMaker Cloud, both the old and the new, runs on the Amazon Web Services infrastructure. Just like any cloud service, your database is physically located somewhere far in a huge data center. While FileMaker Cloud 1 (now called FileMaker Cloud for AWS) can be deployed in several AWS locations, including several in Europe and Asia, FileMaker Cloud 2 (called simply FileMaker Cloud), initially only uses data centers in the U.S.A.

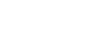

So when connecting to the server and performing operations on the client, involving communication with the server, I did expect the distance, and thus network latency, to be the biggest performance denominator. My test results in this area were not surprising at all.

This should be a reminder that one of the key considerations when moving your app to the cloud in general should be whether you have it properly optimized for WAN performance. This includes many small things with one common question to ask. For whatever you do within the app, ask yourself: "How many times does FileMaker Pro (Advanced) have to send any query to FileMaker Server and wait for its response in order to perform this operation?" Minimizing this quid-pro-quo chatting between the client and the server is the key.

The Nice Surprise

Since the impact of latency was pretty obvious, my following tests focused on the computing and processing power of the FileMaker Cloud. And to make my test results close to what an average small business starting with the FileMaker platform can expect, I intentionally used the smallest available instances, coming as default with the 5-user license, and compared them to the Mac Pro I have been used for my performance tests for the last 4 years.

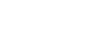

To eliminate the latency impact, all these tests were executed via Perform Script on Server, and to simulate multiple simultaneous users, I was running 5 or 15 server-side scripts at the same time. I also compared FileMaker Server 18 with and without the startup restoration (and page-level locking) enabled.

This chart has very nicely surprised me. Not only with the fact that FileMaker Server 18 seems faster than FileMaker Server 17 even without startup restoration enabled, but also with that both clouds can be really comparable, even in the entry-level configuration, to a standalone hardware server in terms of accessing and exporting data.

The Not So Nice Surprise

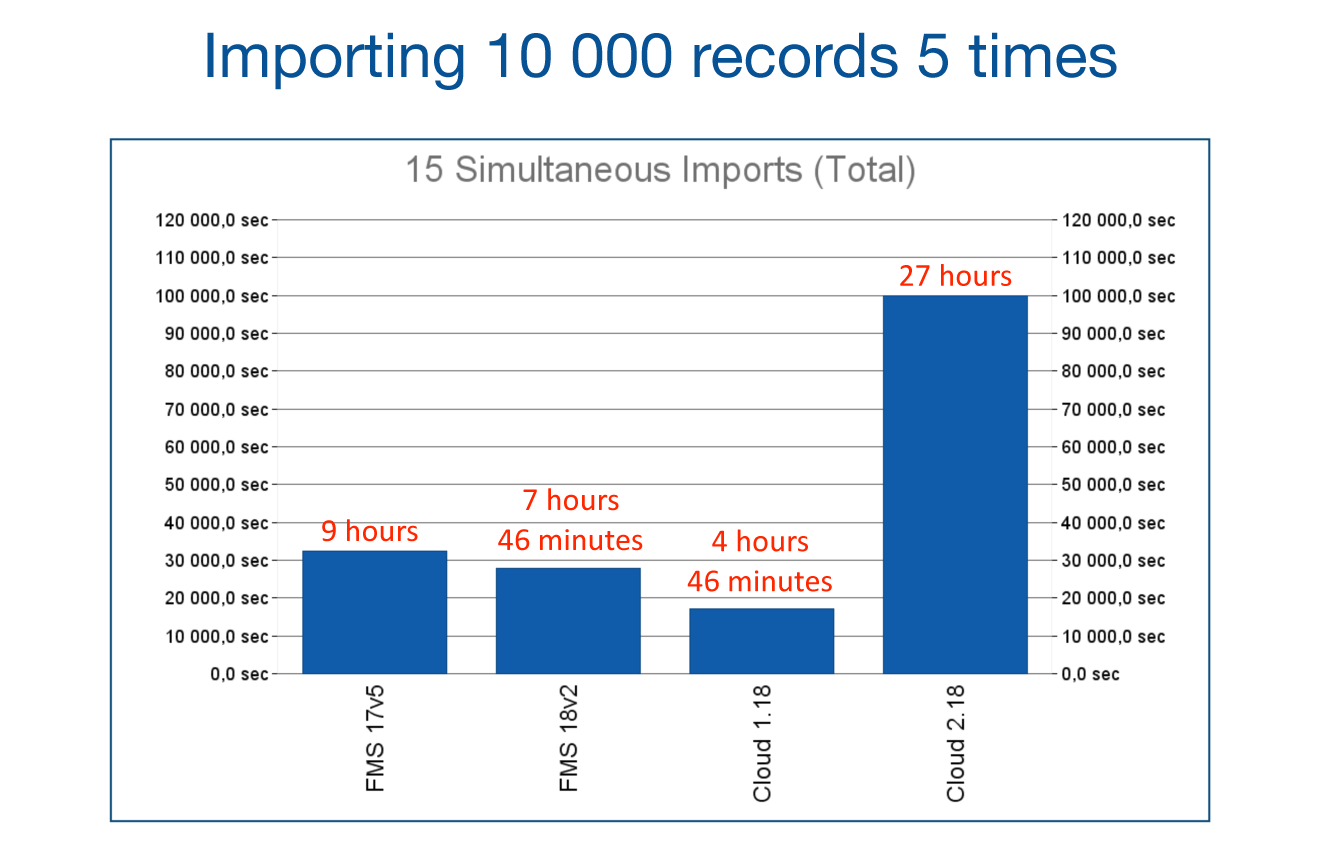

As my automated tests were running though, I started to be nervous. Especially when my complete test set which easily finished in about 9 hours on my Mac Pro and less than 5 hours on FileMaker Cloud for AWS, was not yet finished in the night before my conference session, after running for 20 hours on FileMaker Cloud 2.

I needed some explanation because I could not believe the new FileMaker Cloud would be so much slower than the old one, especially when supposedly running on the exact same kind of AWS EC2 instance. So I contacted the technical brains in Claris behind FileMaker Cloud and after exchanging few e-mails I learned probably the most important aspect of cloud computing I should be aware of.

Meet CPU Credits

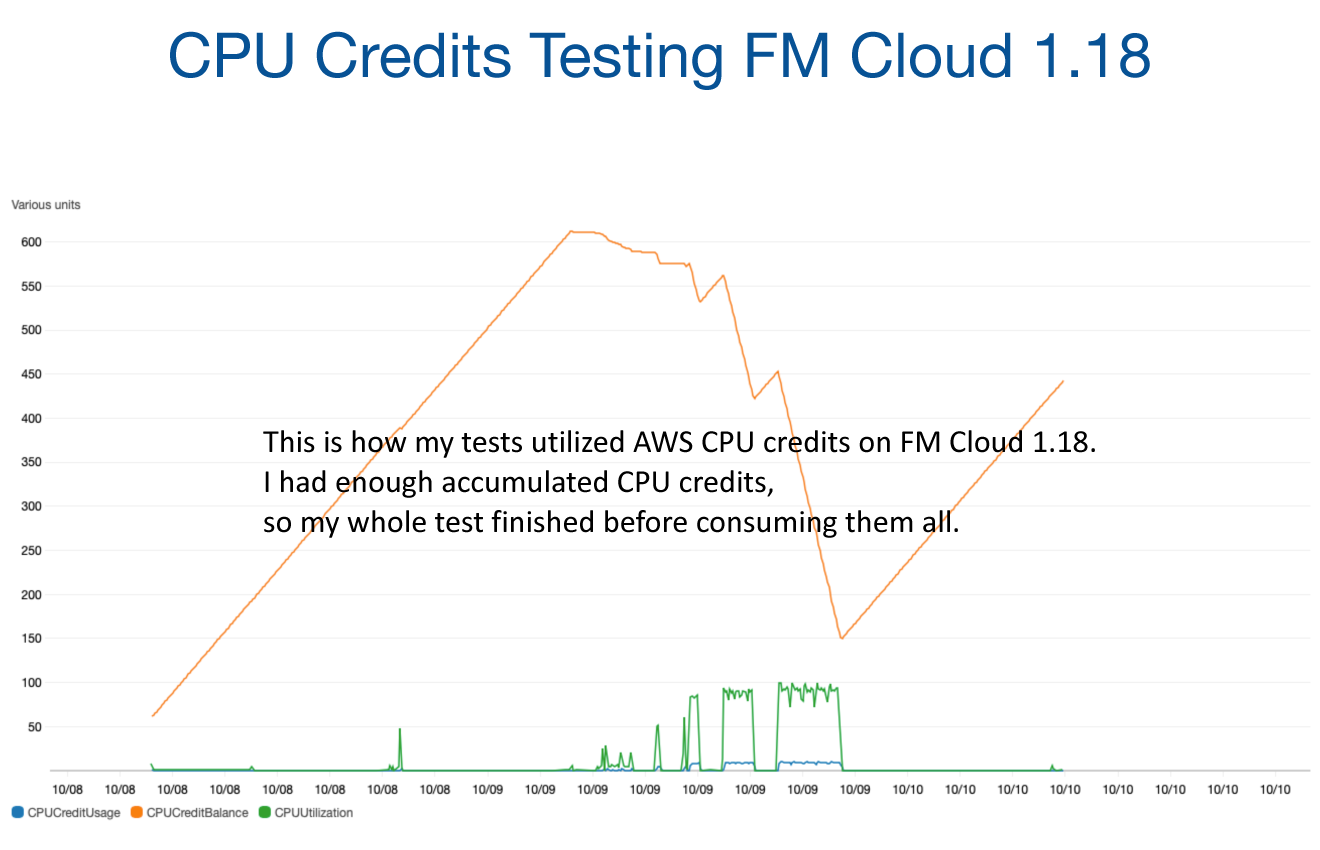

In order to offer so called burstable computing power to handle occasional requests very fast at reasonable cost, AWS uses a thing called computing credits. The way it works is that the more work the server is doing the more credits it is consuming. When you're utilizing less than defined baseline performance of the cloud instance, you're accruing credits to use when you need more work. When I was going to run my tests on FileMaker Cloud for AWS, I turned on the AWS instance, but got interrupted by other tasks, so I let it sit idle for several hours before I actually started my tests.

This is what it looked like in terms of accruing and consuming computing credits:

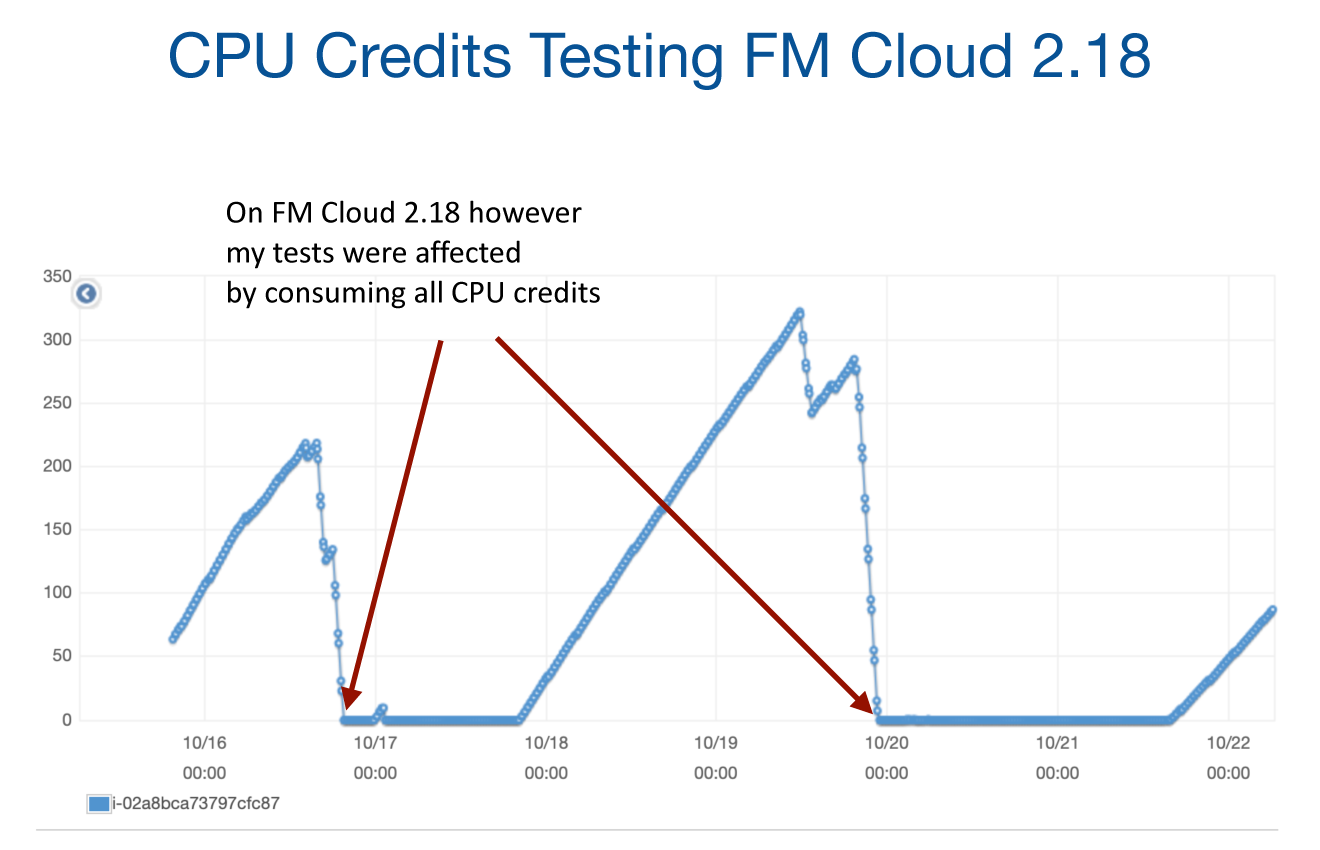

The point is that I accrued enough to power the complete test set without running out of credits. With the new FileMaker Cloud, however, I was so much running out of time that I wanted to save every minut, and started my tests almost immediately after getting access to the trial. So contrary to FileMaker Cloud for AWS I actually did not allow the FileMaker Cloud 2 instance to accrue almost any CPU credits at all. So I learned the hard way what happens when I consume all the credits.

Thanks to the support people from Claris I got this chart showing what my CPU credits utilization actually looked like:

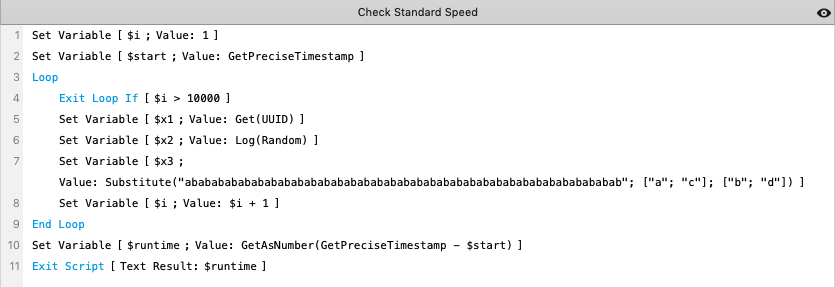

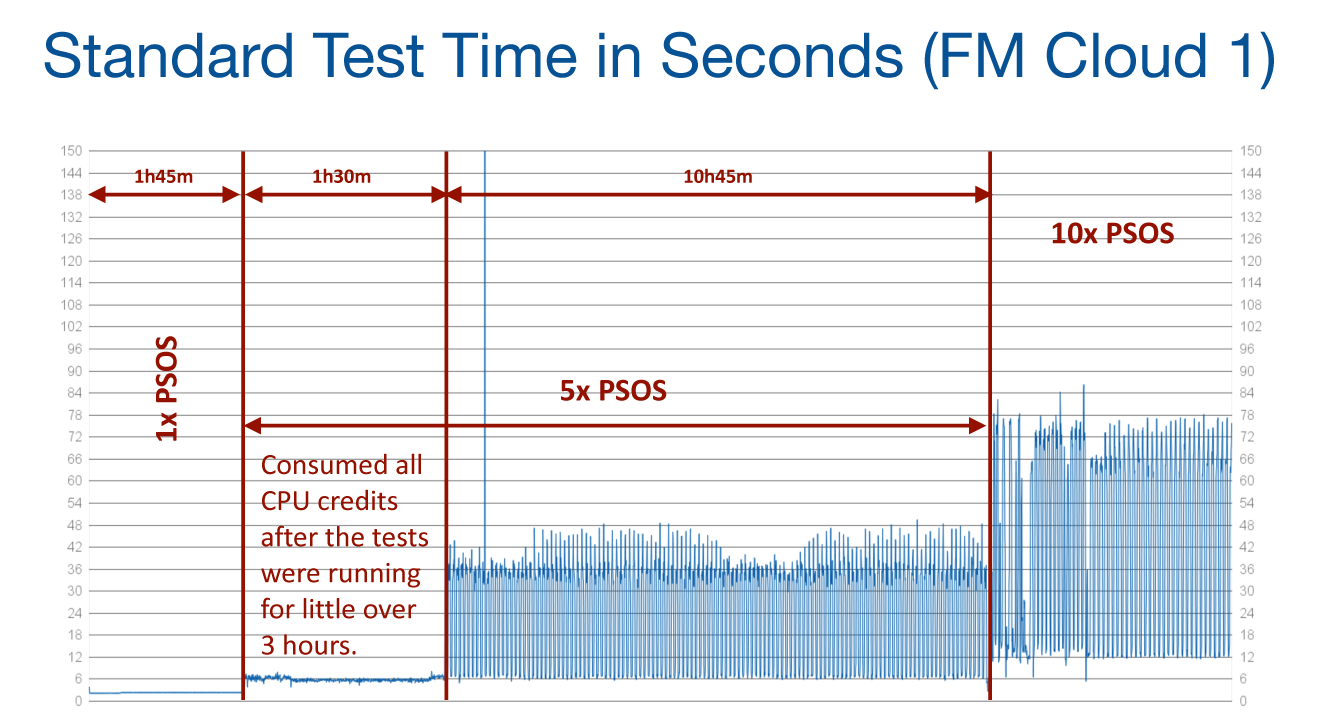

This made me curious what I should expect if I actually run out of credits. So I created a simple script that did not have to touch data tables and only solely consumed power by performing calculations. Then I started another series of tests, where this "standard" test was inserted after every test from my set, simply to measure what actual processing power my instance got awarded at what time.

After performing my set of tests again, the results of both versions of FileMaker Cloud were similar. What was very interesting though was how the cloud was protecting other customers against me consuming all its power.

This way I learned not only what the cost of the "performance bursts" is, but also that a server-side script running in a loop can probably consume all the CPU credits much faster than any other kind of database operation.

The Outcome

Cloud computing is not only trendy these days. It can certainly offer some unique values. But it requires different way of thinking when developing software. You can utilize a lot of processing power, but you have to either limit that to very short bursts, or be ready to pay for upgrading your instance. So if you're going to make your FileMaker app ready for FileMaker Cloud, I suggest you not only optimize it for WAN access by using server-side scripts to minimize client-server chatting, but also avoid doing too much processing in the server-side scripts at the same time.